- The Passover Story

- A Walk Through the Seder

- The Messianic Connection

- Free At Last

- CJFM Passover Seder Schedule

- Host Your Own Seder

Free at Last

Order these

resources from MessianicSpecialties.com

By Dr. Gary Hedrick

Originally published in the Mar/Apr 2011 Messianic Perspectives.

The universal cry for freedom is a refrain that’s been repeated—in one form or another—throughout the history of the human race.

The Jewish people are no exception. They have their own narrative about freedom. It’s known as Passover, sometimes also called the Festival of Freedom.

This observance takes us back to the mid-15th century BC, when the children of Israel were slaves in Egypt. The Egyptians had become cruel taskmasters, and Pharaoh exploited the Hebrews ruthlessly as laborers on his massive building projects.

This observance takes us back to the mid-15th century BC, when the children of Israel were slaves in Egypt. The Egyptians had become cruel taskmasters, and Pharaoh exploited the Hebrews ruthlessly as laborers on his massive building projects.

Finally, when they didn’t know what else to do, the Jewish slaves cried out in desperation to God:

. . . Then the children of Israel groaned because of the bondage, and they cried out; and their cry came up to God because of the bondage. So God heard their groaning, and God remembered His covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. And God looked upon the children of Israel, and God acknowledged them (Ex. 2:23-25).

God heard the cries of His people and He would send them a deliverer. But who would it be? If the choice had been ours and we were collecting résumés, here’s how the classified ad might have read:

Wanted

Young and energetic executive sought for long-term, upper-level management position. Must have local roots, impeccable credentials, and a clean record. Preference given to risk-takers with experience handling snakes. Aptitude and experience in public speaking a plus.

Reply c/o Box 777, The Rameses Times

Now let’s look at the LORD’s choice—Moses. He met almost none of the qualifications. He was (1) elderly (80 years old; Ex. 7:7), (2) a fugitive from justice (Ex. 2:11-15), and (3) not good with words (Ex. 4:10).

But this is how God often works. He chooses the least likely candidate. We tend to look at superficial characteristics; but He looks at the heart. He knows that inward character is more important than outward traits. Centuries later, that’s why He would select David—the obscure shepherd boy—to be king over Israel (1 Sam. 16:1-13) instead of Saul—the tall, handsome, and famous war hero.

The First Passover

We all know the story. Moses’ parents are Hebrews; but through a strange turn of events, he’s adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter and grows up in the royal court. When he’s approximately 40 years old, Prince Moses kills an Egyptian official while defending a Hebrew slave. Once he realizes that he won’t be able to conceal his crime, he flees across the rugged Sinai wilderness to Midian, where he goes into hiding for 40 years. Then God speaks to him from a burning bush and tells him to return to Egypt and lead His people to freedom.

Moses is quaking in his sandals—but he obeys. He returns to Egypt and confronts Pharaoh with a message from Yahweh, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob: “Let My people go” (Ex. 5:1). Pharaoh knows that without all of the Israelites’ free labor, the Egyptian economy could collapse—so he refuses.

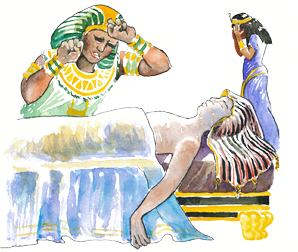

The LORD decides to incentivize the stubborn king. He sends a series of 10 devastating plagues on the land of Egypt. The last one is the death of the firstborn of every household—including Pharaoh’s palace. Because the Israelites followed God’s instructions and brushed the blood of lambs on the doorframes of their dwellings, the Destroyer “passed over” them (hence, the term “Passover”). Finally, cradling the limp, lifeless body of his own son in his arms, Pharaoh relents.

The LORD decides to incentivize the stubborn king. He sends a series of 10 devastating plagues on the land of Egypt. The last one is the death of the firstborn of every household—including Pharaoh’s palace. Because the Israelites followed God’s instructions and brushed the blood of lambs on the doorframes of their dwellings, the Destroyer “passed over” them (hence, the term “Passover”). Finally, cradling the limp, lifeless body of his own son in his arms, Pharaoh relents.

The children of Israel depart in haste from Egypt (something they had been warned to anticipate)—but their ordeal isn’t over. Pharaoh changes his mind and pursues them. With the Egyptian army quickly descending on them, the defenseless Israelites arrive on the banks of the Red Sea. There is nowhere else to go but straight ahead; although the water blocks their way. Moses prays and then uses his staff to part the sea miraculously. As the people watch with wide-eyed, open-mouthed astonishment, a path opens up before them. They flee to safety with walls of water suspended on either side of them. When the Egyptians try to follow, the water comes crashing down and they drown.

The Four Ds of the Passover Narrative

It’s an exciting and compelling story, to be sure. However, it’s much more than just a story. It’s also a teaching tool. Through the Passover narrative, God teaches us a great deal about Himself—and about ourselves.

1. The Danger of Complacency

The children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob actually did pretty well in Egypt—at least, for a time.

So Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt, in the country of Goshen; and they had possessions there and grew and multiplied exceedingly (Gen. 47:27).

That, in fact, was the problem. Originally, the people of Israel had gone to Egypt to escape a famine. It should have been only a temporary move. After all, Canaan was the Promised Land—not Egypt.

But they prospered in Egypt. Because of their relationship to Joseph, the Israelites were a privileged group. It was a comfortable life. They even came to fancy the cuisine (Num. 11:5).

So they just never seemed to get around to going back to Canaan. Whenever the subject came up, I suppose they just said, “Maybe next year.”

It took a change of administration (and a new Pharaoh who didn’t like them) to shake the Israelites out of their complacency.

Aren’t we the same way? We get comfortable with our jobs, a house in the suburbs, and the ability to pay all our bills—and before too long, we start thinking we don’t need God anymore.

Then a “famine” hits—like the Wall Street disaster that struck the United States in 2008—and we don’t know what to do. We lose our jobs (and insurance benefits) and the banks foreclose on our homes. Hard-earned investments disappear into thin air. Unpaid bills start to pile up.

Then a “famine” hits—like the Wall Street disaster that struck the United States in 2008—and we don’t know what to do. We lose our jobs (and insurance benefits) and the banks foreclose on our homes. Hard-earned investments disappear into thin air. Unpaid bills start to pile up.

In desperation, like the ancient Israelites, we cry out to God for help. That’s when He knows He has our attention.

Very often, what we see as a tragedy or disaster is actually a wake-up call from the LORD. It’s His way of getting our attention. That was true in the days of the Exodus and it’s still true today.

2. The Delusion of a Secular Worldview

When the people cried out to God, I’m sure there were doubters among them who said, “So you think Abraham’s God is going to help us? Good luck with that!”

It had been a little more than 400 years since their forefathers fled to Egypt to escape a horrible famine in Canaan (Gen. 47:1-27). Now, four centuries later, this was a generation who had never witnessed a miracle. They hadn’t heard the voice of God. So they had no frame of reference for anything miraculous. For all intents and purposes, they were materialists with a secular worldview.

The same thing is happening today. Secularists and materialists have claimed the culture for themselves. To them, the physical universe is all there is. Everything evolved from primordial molecules and atoms as a result of natural forces. The secularists finally figured out that they don’t have to prove God is a myth (like their forerunners, the “free-thinking” atheists, tried to do); all they have to demonstrate is that He is unnecessary.

I’d say they’ve done it pretty well because materialism has become a dominant worldview in our culture. It’s taught (or worse, simply assumed to be true) in our academic institutions and it’s reflected in the arts and media. So when secular (non-religious) people hear us talking about the miracles God did in the Bible, they think we’re talking about magic and fairy tales. They have no frame of reference for anything else. A secular worldview comes as naturally to them as barking does to a dog.

This is why every believing parent’s primary responsibility is to convey a biblical worldview to his or her children. Our children, and our children’s children, need to know what God has done in the past—and what He will do in the future. Biblical accounts like the one in Exodus, where Moses recounts how God miraculously delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt, provide that needed frame of reference.

Only take heed to yourself, and diligently keep yourself, lest you forget the things your eyes have seen, and lest they depart from your heart all the days of your life. And teach them to your children and your grandchildren (Deut. 4:9).

3. The Devastation of a Broken Spirit

One of the saddest verses in the Bible is Exodus 6:9: “So Moses spoke thus to the children of Israel; but they did not heed Moses, because of anguish of spirit and cruel bondage.”

The term “anguish” in this verse translates a Hebrew word that means “to cut off,” like stalks of grain are cut down by a farmer at harvest time. “Anguish of spirit,” then, describes people who’ve been cut down or broken by their circumstances. It tells us that the Israelites had been beaten down for such a long time that they didn’t care anymore. Their spirits were broken.

When Moses stood up and told the children of Israel that the LORD had heard their cries and they were about to experience His miraculous deliverance, most of us would have expected them to jump up and down with joy and anticipation! But the Bible says they didn’t respond because of their brokenness.

However, one of the paradoxes of the Christian life is that God is often closest to us when He seems farthest away: “The LORD is near to those who have a broken heart, And saves such as have a contrite spirit” (Psalm 34:18).

That was certainly the case here. In these opening pages of Exodus, as bleak and hopeless as things appeared to be, the stage was being set for one of the greatest miracles—a whole series of miracles, really—in the history of the human race. A broken and demoralized nation was about to witness the salvation of the LORD. This leads us to the fourth “D.”

4. The Deliverance of God

We saw earlier that when the Israelites cried out to God, He remembered His covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That covenant—the terms of which are scattered through several passages in Genesis (e.g., 12:1-3, 7; 13:14-17; 15:121; 17:1-8)—became the basis for His response.

What moved God here was not merely the fact that people were suffering; after all, multitudes of people are suffering all over the world at any given point in time—and He has compassion for all of them. But He generally allows events to run their course without His intervention because everyone suffers the consequences of living in a fallen and broken world. So why did He intervene for the children of Israel?

The children of Israel were set apart from everyone else because God had previously made them (through their forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) specific promises. These were not promises ultimately for their own benefit, but for the benefit of the entire human race. He was going to use them to bless the world in more ways than anyone in the 15th century BC could have imagined. Yet here they were, under attack by a brutal king and demoralized to the point where many of them didn’t even want to live anymore—and with their continuance as a nation in question.

So when God heard their cries, He was moved to action because they were uniquely His covenant people. He had chosen them for a very special mission. That’s why He identified Himself to Moses as “the LORD God of their fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (Ex. 4:5).

God had promised Abraham three things:

God had promised Abraham three things:

(1) a physical territory, (2) a seed (i.e., a son and descendants, including the ultimate Seed—the Messiah), and (3) blessings that would flow both to and from him.

The geographical aspect of this covenant was later amplified in the Land Covenant (Deut. 30:1-10); the seed aspect was expanded in the Davidic Covenant (2 Sam. 7:8-16); and the blessings aspect comes to fruition in the New Covenant (Jer. 31:31-36).

If Israel as a people (Am Yisrael) had been either destroyed by or assimilated into Egypt, the consequences would have been disastrous.

That’s why the LORD rolled up His sleeves and went to work in Egypt on their behalf (cp. Isa. 52:10). The covenant had to be honored. The promises had to be kept so the mission wouldn’t be jeopardized. Israel had to survive so she could be a light to the nations and so the Messiah could be born.

Passover and Salvation

Passover isn’t solely about physical deliverance; it’s also about spiritual deliverance. The story of the Exodus, in fact, can be seen as an allegory of salvation.

Looking at the Exodus through this grid, Egypt symbolizes the world. Everyone in the world (Egypt) is under the dominion of sin and the devil (Pharaoh). God calls His people (Israel) out of the world, and promises to deliver them if they trust Him. The blood of the Messiah (the lamb) is what makes that redemption possible.

When we follow the LORD by faith (like Israel did when she crossed the Red Sea), He protects us (as seen in the destruction of Pharaoh’s army), leads us (the cloud by day and the pillar of fire at night), fellowships with us (the Tabernacle), instructs us (the Torah given at Mt. Sinai), provides for us (manna)—and our ultimate destination is Heaven (Canaan).

Nevertheless, even after we’re saved (delivered), we sometimes hear the siren call of the world (Egypt). We might even wonder if we made a mistake by leaving the old life behind.

Keith Green, a Jewish believer whose musical career was cut short by a tragic airplane crash in 1982, made this temptation the theme of his song “So You Wanna Go Back to Egypt”:

So you wanna go back to Egypt, where it’s warm and secure.

Are you sorry you bought the one-way ticket when you thought you were sure?

You wanted to live in the Land of Promise, but now it’s getting so hard.

Are you sorry you’re out here in the desert, instead of your own backyard?

Eating leeks and onions by the Nile. Ooh what breath, but dining out in style.

Ooh, my life’s on the skids, give me the pyramids.

Well there’s nothing to do but travel, and we sure travel a lot.

‘Cause it’s hard to keep your feet from moving when the sand gets so hot.

And in the morning it’s manna hotcakes.

We snack on manna all day. And they sure had a winner last night for dinner, flaming manna soufflé.

(For more on his ministry visit www.keithgreen.com.)

Can you imagine dining from the same menu every day for 40 years? So it’s true—sometimes we’re tempted to return to “Egypt.” But no one ever said this was going to be easy. At times, it takes every bit of strength we can summon just to put one foot in front of the other so we can keep on going.

Nonetheless, we persevere by God’s grace, and continue trusting the One who called us. Over time, we build momentum. He blesses and empowers us; and we know eventually we’ll come to the Promised Land.

Passover and Prophecy

It is no mere coincidence that Yeshua (Jesus) died during the Jewish Passover observance in (or around) AD 30 (Matt. 26:2).

God planned it that way because His Son fulfilled the symbolism of Passover.

The Apostle Paul said, “[Messiah], our Passover, was sacrificed for us” (1 Cor. 5:7).

Yeshua was like the Passover lamb in several ways:

- He needed to be flawless (Ex. 12:5; cp. John 18:38, Heb. 4:15);

- He had to die (Ex. 12:21; cp. Rev. 5:6-12);

- He didn’t resist (Isa. 53:7; cp. Matt. 27:12-14);

- He was a substitute (Ex. 12:3; cp. John 1:29);

- His shed blood had (and still has) power to save (Ex. 12:21-27; cp. 1 Peter 1:18-19); and

- He saves those who trust Him and apply His blood, symbolically and by faith, to the “doorframes” of their hearts (Ex. 12:22; cp. Heb. 11:28).

However, the analogy of the Passover lamb doesn’t stop at Yeshua’s first coming. It’s also found in Second Coming contexts. In the Book of Revelation, for instance, the glorified Messiah is seen repeatedly and symbolically as a “Lamb” (Rev. 5:6, 8, 1213; 6:1, 16; 7:9-10, 14, 17; 12:11; 13:8; 14:1, 4, 10; 15:3; 17:14; 19:7, 9; 21:9, 14, 22-23, 27; 22:1, 3). The victorious Lamb metaphor anticipates the Messiah’s triumphant Second Coming while also reminding us of His role (in His first coming) as a suffering Savior, who was mocked and ridiculed while going willingly to His death.

This Lamb in Revelation, however, is unlike any other lamb you’ll ever see. He’s not the quiet, submissive Lamb who’s presented in the Gospels—or the ones that were hurriedly killed in Egypt. Here in Revelation, the slain Lamb has been resurrected (5:6-13), and no one is messing with Him now. They’re not mocking or beating Him anymore because they’ve seen His power and they’re scared out of their wits (6:16). He’s no longer meek and submissive. Now He’s a Warrior (17:14) and He has a throne (22:1).

The Lamb who was slain is now the Lamb who reigns forever:

And every creature which is in heaven and on the earth and under the earth and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them, I heard saying: “Blessing and honor and glory and power Be to Him who sits on the throne, And to the Lamb, forever and ever!” (Rev. 5:13).

And every creature which is in heaven and on the earth and under the earth and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them, I heard saying: “Blessing and honor and glory and power Be to Him who sits on the throne, And to the Lamb, forever and ever!” (Rev. 5:13).

The Passover Lamb has a dual identity because He is also our soon-coming Lion of the tribe of Judah (5:5). A helpless, defenseless lamb and a dangerous, carnivorous lion—now that’s quite a study in contrasts! It’s not so much a mixing of metaphors as it is a blending of prophetic symbols—and it makes the point powerfully.

Passover and Freedom

Freedom has both negative and positive aspects. Negatively, we are freed from something; positively, we are freed unto (or for) something else.

For ancient Israel, Passover meant they were freed from slavery (and ultimate doom) in Egypt.

They were also freed to rekindle the relationship their forefathers had with Yahweh before they had deviated from His will by fleeing to Egypt 400 years earlier.

For believers today, Passover means we’ve been freed from the bondage of sin (and ultimate doom) by trusting in the shed blood of the Messiah.

It also frees us to enjoy a personal relationship with the Creator of the universe.

What could be more fulfilling than getting to know the One who made you?

It’s hard even to imagine such a thing; yet the Bible says it can happen (Phil. 3:8; John 3:16-17). The Bible says, “Therefore if the Son makes you free, you shall be free indeed” (John 8:36).

This is why God’s message for the world is known as “Good News”:

The Spirit of the Lord GOD is upon Me,

Because the LORD has anointed Me

To preach good tidings to the poor;

He has sent Me to heal the

brokenhearted,

To proclaim liberty to the captives,

And the opening of the prison to those

who are bound

(Isa. 61:1; cp. Luke 4:18).

If you’d like to know more about this Good News, please call, write, or email us today.